Coyote Valley History

Ancestorial Territory

The Pomo people have lived in the areas of Mendocino, Lake, and Sonoma counties for many millennia, denoting the thousands upon thousands of years our people have lived and thrived in the area now known as Mendocino County. These people differentiated themselves in many ways, one such being their language. By dialect these people are further broken down as Northern, Central, Eastern, Northeastern, Southeastern, Southern, and Kashaya (Southwestern) peoples who spoke the same languages over a range of their territories. The Pomo people were weavers, famous for their beautiful basketry, healers, whose songs and ceremonies called upon divine and sacred healing powers, and a peaceful people, who made many connections with surrounding indigenous groups who bordered their greater territory. Oral traditions strengthened communities, stories of creation, of the natural world, and of the spirits that lived alongside the people. The Sho:daxay (Shodakai) Pomo, our people, originate in the northern territory alongside the Russian river of the Pomo homeland, the dialect predominately of Northern Pomo.

Map of the Pomoan languages (Walker 2020). “Northern Pomo.” California Language Archive, cla.berkeley.edu/languages/northern-pomo.html.

The 1800's

-

Nestled in the foothills alongside the east fork of the Russian River, Coyote Valley was one of several valleys running along the river’s many branches. In the 1800s, it was described as being “all brush,” a “bare trace of land, where nothing grew, no trees or shrubs, just grasses.” However, a thriving population of Indians lived in this valley long before settlement occurred and still inhabited the area when the first non-Indians came.

-

In 1835, Spanish troops led by Captain Sepulvedo Vallejo came to procure Indians from Coyote Valley and the surrounding area, to work on houses and forts being built at Sonoma, followed soon after by expeditions to procure Indian children as slaves. Coyote Valley, Calpella, and Redwood Valley were “settled” sometime early in the 1850’s as part of the township of the Ukiah and hence divided into grants of land and farms.

-

On December 10, 1878, a group of Indians of the Ca-ba-kana, Pomo, and Katca tribes of Redwood Valley bought seven acres of the land in Coyote Valley for two hundred dollars. The land was mostly flat and extended to the western edge of the property and was part of Riverside Ranch, a large ranch owned by Lucius Byron Frasier. Title to the Old Rancheria was held in common by the “Redwood Valley Tribe.” Although eighteen men were listed in the deed as owners, it appears that there were usually no more than five or six families living there at any given time.

-

The Indians of Coyote Valley rejected housing provided by the ranchers and preferred to live in “grass homes” on their own property, but some wooden houses also stood on the land. These homes were made of rough redwood board and batten construction. There were few windows, and in some cases, the houses were without doors. Their homes did not have running water, unlike the homes of their non-Indian neighbors. The Indians would pack buckets of water to their homes from the river or from a year-round spring located near their homes.

_edited.jpg)

_edited.jpg)

Early 1900's

-

In 1909, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) purchased land in Coyote Valley for the benefit of the Indians of the Ukiah Valley. The land, known as the Coyote Valley Rancheria, was made up of 101 acres and consisted of three distinct sections: rivers bottom, sloping hillside and a flat terrace land overlooking the river. According to residents of the Rancheria, there were live oaks and white oaks growing in isolated and dense groves on the bottomland. It was “open in places, rocky grasslands also in other places and poison oak all over.”

-

The traditional diet of the Coyote Valley Rancheria residents underwent change long before the establishment of the Rancheria in 1909. Residents stated that whites had essentially destroyed traditional sources of clover and acorns and only a few were left accessible to them. Deer were scarce, but the fishing remained good. No livestock other than poultry were kept on the Rancheria. During the summer, deer were hunted in the hills around the valley. For the most part, however, residents depended upon stores in Ukiah as the major source of food. Residents’ memories of buying dry goods in Ukiah were not pleasant.

-

By the early 1920s, it appears that eight individuals held assignments on the Coyote Valley Rancheria. In the mid-1940s, nine field assignments were issued for agricultural and related activities; three of the assignments were issued to residents who already had house assignments there, while six were issued to residents of Pinoleville.

-

As with most Indians throughout the country, Coyote Valley Rancheria residents were discriminated against in the Ukiah Valley. Stores in town would not allow Indians to try on ready-made clothing, which meant they had to take a trip to Santa Rosa if they wanted to try on clothes before purchase. They were not served in local beauty parlors, and only one restaurant, run by a Chinese family, would accept Indian patronage. The local movie theater permitted Indians to sit only in the balcony. In the 1920s, a number of residents attempted to enroll in local schools. One resident recalled, “They didn’t allow Indians,” although there were occasional exceptions. Coyote Valley Indians attended an Indian school in Pinoleville as well as the Sherman Institute in Riverside, California, and Chemawa Indian Training School in Oregon.

-

Four Indian men attempted to steal wine from the storage facility of an Italian grape grower. When the grower confronted them, he was fatally shot. All four men were indicted and brought to trial. Three were convicted and received lengthy prison sentences.

-

The fourth, an Indian from the Old Rancheria, was found not guilty. Their defense was conducted by Ukiah lawyer Arthur "Wessels", whose fee was $250.00 at 8% per year payable in two years. The promissory note was signed on January 26, 1924, and was secured by a mortgage on the Old Rancheria. The young Indian families were unable to pay the principal or interest on the note. Wessels eventually assigned the lot to Mrs. Susan Husted of Ukiah for $250.00. Finally, on January 27, 1928 the court issued a decree of foreclosure and order of sale. On April 21, 1928, by order of the court, the land was sold on the steps of the courthouse to the highest bidder for the sum of $376.50.

-

By the 1940s, this discrimination had, in the main, ended largely due to the efforts of the Pomo Mothers Club.

-

Employment was usually seasonal. Men, women and older children picked fruit and hops from March to July and grapes and pears from September to October. In the early years, women were not allowed to pick pears since it was considered too difficult. Some women did laundry and housekeeping for white families, but from November to March there were usually no significant income at all for any of the Rancheria’s residents. For men as well, winter offered few employment opportunities. In need for a mechanism, whereby Coyote Valley Rancheria residents could regulate their own business activities, 12 members passed the constitution and by-laws for a regulatory organization. On May 27, 1947, The Growers of the Coyote Valley Rancheria Association was formally organized.

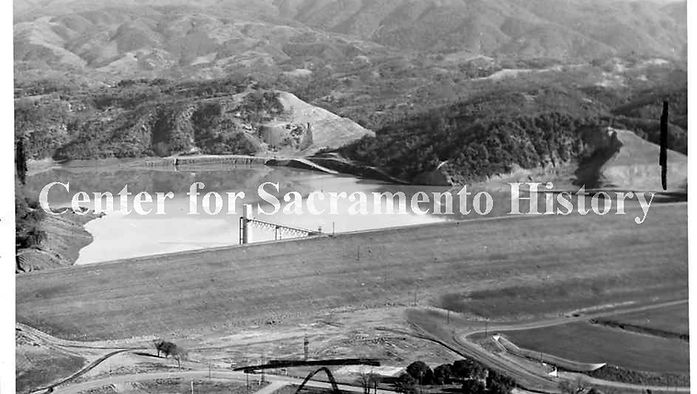

This photo depicts a view of what is now known as the Bushay Recreation Area and Eastside Trailhead area of Lake Mendocino before the Pomo Indians were removed for the development of the Russian River dam. (1953)

_edited.jpg)

Mid 1900's

Diane-Ortiz, Altheia Campbell-Ortiz, Hannah Ortiz, Janet Ortiz-Mulhorn, Josephine Campbell-Bernard, Altheia Ortiz-Magana

-

In a report produced in 1951 by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Rancheria was described as having three distinct levels. The first level, located on the main highway, was the location of the homesites. The seven or eight houses, all constructed by the Indians themselves, were in good condition with electricity in all the houses. The second level was agricultural with about 13 acres of the vineyard being farmed by members of the Pinoleville Rancheria. The report also indicated that there were two wells on the Rancheria, a spring providing one family with freshwater and one water tank with a holding capacity of six thousand gallons.

-

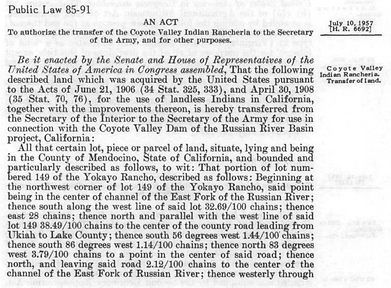

Ten years after the sale, the status of the Coyote Valley Indians came up again. Although the bill HR 6692 specified that Coyote Valley’s status as a recognized tribe was “terminated,” the Indians believed there tribal status was illegally destroyed.In 1973, James F. King, an attorney with the California Indian Legal Services, wrote to the BIA in Sacramento on behalf of the Coyote Valley Indians, inquiring as to the specific legal authority for the condemnation of the Coyote Valley land and the termination of their tribal status.On February 20, 1976, a final declaratory judgment and permanent injunction was issued by action of Eddie F. Knight versus Thomas S. Kleep and by Judge W. I. Sweigert, United States District Court, North District of California (Actions 73 – 0334; 74 – 0005). This judgment declared that termination of the Coyote Valley Rancheria in 1957 was invalid and that the government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Coyote Valley Pomo, as documented on the various Rancheria distribution plans, continued to exist.

-

The Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians regained their status as a recognized tribal group. Thus, in 1976, the Coyote Valley Tribal Council was organized for the primary purpose of regaining a land base for the band and to promote the economic and social welfare of its members. On October 3, 1980, the General Council ratified the governing document entitled, The Document Embodying the Laws, Customs and Tradition of the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians.Prior to the late 1970’s, the tribe had begun looking for property that would be suitable for a residential community. A Community Development Block Grant was awarded to the tribal community from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 1979, to purchase a 52 to 76 acre parcel in Redwood Valley, California. The land was taken into Federal Trust status the same year. A Secretarial proclamation declared this new tribal land to be a federally recognized Indian reservation.1 Carpenter, Aurelius O., and Percy H. Millberry. “Early Settlement.” History of Mendocino and Lake Counties, California, with Biographical Sketches of the Leading, Men and Women of the Counties Who Have Been Identified with Their Growth and Development from the Early Days to the Present. Los Angeles, Cal.: Historic Record, 1914. 70. Print.2 Carpenter, Aurelius O., and Percy H. Millberry. “The Grant.” History of Mendocino and Lake Counties, California, with Biographical Sketches of the Leading, Men and Women of the Counties Who Have Been Identified with Their Growth and Development from the Early Days to the Present. Los Angeles, Cal.: Historic Record, 1914. 82. Print.

Present Day